I Found Europe in Dakar

Europe, and its supposed mid-life crisis has been a popular press topic as of late. I have observed in-depth features and lengthy articles in the output of as widely disparate media as the BBC, the Economist, and Al-Jazeera. Where is Europe heading? and What does it mean to be European? seem to be the questions of the day, and with the French elections around the corner, the debate is unlikely to quiet down anytime soon.

Leaning out of the window as the Bamako-Dakar Express clattered into the capital of Senegal, my eyes resting on crudely built shanties one minute and tall, clean colonial houses the next, I did not expect Dakar to provide me with new perspectives on the meaning of European.

Once in central Dakar, after bargaining dutifully for a taxi fare outside a dark train station, dragging my bag through deep sand, and avoiding the looks of long-legged prostitutes at my hotel, I wandered the streets. I assumed that a block or two in either direction would take me to something edible, since Mali has a little coal-grill and a lady selling friti or brochetti on every corner. The city quickly made me feel deeply uneasy and strangely at home at the same time, but I couldn't figure out why.

I came across groupings of young white people, stumbling noisily out of bars, laughing. They would disperse, or move on to another bar, and I would keep following the sidewalk, scouting for food. After ten minutes, I realized that I had come across only toubabs during my walk, and thought maybe that was what felt so out of place, yet familiar. The bar-life felt somewhat Mediterranean, and the architecture distinctly French, so that must be it, then. Both the place and the people I had met looked European. Mystery solved. But why did I feel so uncomfortable?

I stopped by a lamp post and looked around. The streets were clean, paved, and -- wow! street lights... I hadn't even thought about the fact that I could see where I was walking. No sewage streams in the street, either, and street lights make streets safer, right, so what was perturbing me?

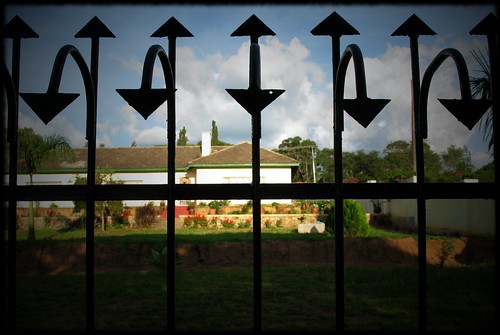

It didn't take me long to give up, both on figuring out what bothered me and on filling my belly. I turned around and turned a corner, walking quickly to try and shake the unease, and almost stepped on an old man lying curled up on a sheet of plastic, sleeping between a road sign and a white-painted fence. And there it was.

The impersonality of it all placed the city in a European mental compartment in my head. Traffic lights and straight, clean streets where only homeless people spend time are European. Sterile and individualistic, they invite you to pass through, but not to dwell. In Bamako, any hour of the day will find tea-making fathers and bare-bottomed babies and football-kicking youngsters in the streets, mingling and talking and being together. And although most people are poor, they are rarely poor alone. Under a plastic sheet or a piece of cardboard and with a streetlight as your sole friend, poverty seems so much deeper, so much more inhumane, so much more like a one-way street.

In many ways, this is not a uniquely European characteristic, but a label that can be placed on most Western cities and societies. Lately, however, Europe seems to be moving rapidly towards an every-man-for-himself value system, and therefore, in my opinion, has earned the dunce-hat.

In Europe recently, every man to and for himself

The newly elected conservative government in Sweden is rapidly undermining long-standing social safety nets by, among other things, insane tax-cuts that benefit a wealthy minority in the Stockholm region and deprive the welfare budget of much-needed funds; most EU countries have placed severe restrictions on the newest members to the union, not wanting to let too many "others" into "our" countries; last I checked, populist, racist, frightening Le Pen had overtaken the centrist Bayrou in the polls, and Sarkozy who also panders to anti-immigrant prejudice looks poised to take the lead in today's first round...

Whatever the French choose, I'm afraid they won't surprise me. Because I've seen Europe; she's sleeping, alone, under a sheet of plastic in Dakar.