Final Watson Report

This is my final Watson report. This does not mean the stories are over, but it is a much-too-brief summary of so many experiences.

When I close my eyes and try to think about this past year as a whole, what pops up is by no means a comprehensive lesson. It is not a cohesive narrative, but rather a collection of smells, of images, of broad horizons and open arms. I did not reach the conclusions I had hoped for, but I am taking with me a web of voices, stories and contradictory opinions. I want to share some of those stories with you.

During much of my time in Mongolia, I traversed landscapes that defied the concept of time as I knew it. I often felt immersed in an ancient drama of isolation and distance, and to the people I lived with, this was their life.

Yandjmaa and Oyundalai are two sisters, who live with their old mother, Enkhtsetseg, and a horde of young children. By moving their household every few months in search of new pastures for the cattle, they conform to the tyranny of the seasons that has sculpted traditional nomadic patterns for thousands of years. Towns, mining prospects and national parks are disrupting this pattern.

Winter is the time of year when most animals die in Mongolia – as well as the longest season. Animals starve or freeze to death, or get taken by the wolves. For Yandjmaa’s family, comprised entirely of women and children, it is by far the hardest season to cope with. While milking a cow in the soft light of dusk, Enkhtstetseg explains how life is getting more difficult: “The most difficult thing about the park is that we now have to go so far to get fire wood.” She sighs, but doesn’t want me to think she is complaining. “We have to find trees that are already lying down, and this takes a long time.”

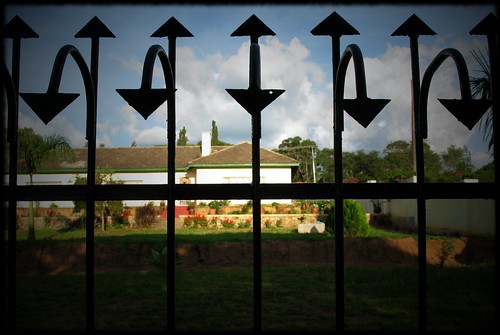

Yandjmaa’s family is poor, and they do not move far. To their south is a little town, where they cannot expect to find good grass, only hostile looks and park officials who treat them as potential criminals. To their north lie rivers that are difficult to cross, and further on a strictly protected area, where park regulations stipulate that no grazing or human habitation is allowed. To the east towers a mountain range, and a large lake blocks any western movement.

In the end, most of the Mongolian nomads I met had not been pushed away from their homes. At times, I became frustrated, thinking that what I was observing and hearing about was somehow not important enough. But little by little, I realized that their lives were affected in subtle, yet fundamental, ways. These were crucial changes; I had simply not been able to recognize them. I began to realize that compassion and understanding do not always come automatically, sometimes they require a conscious decision to place yourself in someone else’s shoes, or bare feet for that matter. I believe that this realization will affect how I relate to other people for the rest of my life.

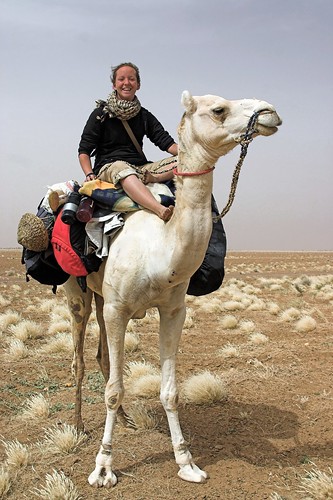

In the West African desert, I learned to always take a second look, as history and destiny spread out over the land like a disguise. Nomads’ lives are governed by the prejudices of others, and by the idea that theirs is a way of life that has become fiction. Wildlife and environmental protection turned out, in practice, to be a non-issue, so what clashed were instead sedentary priorities against those of mobile peoples.

For a while, my project dealt with slightly different issues: I became fascinated with the ways in which mere perceptions could shape policies, and how those policies in turn affected lives. Strikingly, the belief that nomads cannot continue living like they have for millennia leads to initiatives – often designed to improve the situation – that cripple the same people they are supposed to help.

Rahmeta Walet M’Barak lives outside a town that operates on charity, a bit of commerce, and international aid. As I approached her camp, the view was wide, and the land seemed blanketed by a haze of dust, floating not on the wind, but on the dry heat itself. Here, in the middle of the desert, aid projects have encouraged the development of rice fields. Rahmeta, an old woman who relies on her daughters’ husbands for food, can list every aid project that has reached the town since the mid-seventies. The ones that she remembers as the best ones gave out food to every family: milk, flour, grains – everything!

She has begun walking into town on a regular basis to look for signs of aid. “But,” she complains, “we don’t see any aid anymore.” She believes that the aid is reserved to those who live in town. Thus, more and more families have to decide whether to sustain a nomadic lifestyle or move closer to towns where they might benefit from the incredible wealth they perceive is being spread out. Moving into towns is also the best, if not the only, option if they want their children to go to school. Children who are in school need somewhere to stay, so if you don’t have a relative in town, or the money to pay the relative for food, then your whole family must move close to the town during the school year.

I started out this year thinking that I wanted to help nomads, help them by understanding the issues they face, and by trying to communicate my understanding to those in charge, those creating the problems. The problem is that many of the people ‘in charge’ are also trying to help – just not succeeding, not approaching it in the right way. This is by no means a new discovery – I have read about many examples of failed IMF and World Bank policies, that in the end made countries worse off rather than better – but I guess I never believed that these institutions truly wanted to help.

This year has made me recognize that it is not only economic dogmas and ideologies that thwart aid efforts. The slightest flaw in one’s understanding of the dynamics, the history, and the whole picture of a situation, can turn the most well-intentioned aid project into an enemy of those it intended to help.

In Tanzania, colonialism, droughts and national parks have shoved people closer together. In contrast to the other countries I went to, this phenomenon has been thoroughly studied. On the one hand, you might say that my time there was a waste, since I didn’t discover anything ‘new.’ On the other hand, however, it gave me the chance to compare my observations with a relatively extensive literature. In some cases I agreed with the books I had read, in other cases I couldn’t believe they were talking about the same country. It reflected the beauty of the Watson – the possibility to speak with people, to learn about their points of view, without feeling the pressure to draw fixed and final conclusions.

The Tanzanian Maasai, and the Barabaig have lost the majority of their ancestral land. They used to save some of the best grazing land for very dry years, but when the British arrived, they considered it a waste of land and promptly established their farms on that very land. Now, when a drought comes around, which in East Africa it does every seven or eight years, nomads find themselves trespassing when they try to get into their best pastures. Increasingly, nomads are expelled from their pastures, and as they are forced to seek land elsewhere, they in turn create disputes in other places, where other graze their animals. They told me they feel attacked from all sides.

I asked a Barabaig elder, Gitoto, where their dry season grazing is. He looked at me and gestured to the right. "This is a national park" He pointed to the left "Over there is also a national park" He looked straight ahead, where excavators were digging in the ground, puffing out clouds of white smoke. "We had to apply to the local government to live here. Before, we didn’t have to ask anyone where to go. Now this phosphor mine has been sold to Asians, who want to take all of this land too. We have nowhere to go. Nowhere.”

I set out on my Watson wanting to learn, to understand, maybe even to reach some conclusions. What I ended up with is a wealth of faces, of voices, of fragments of life stories. I am no wiser, but I think I am more human. My heart is filled with connections to other hearts, and I will carry these connections with me for the rest of my life.

As I look back, I can only think that ignorance, not knowledge, is cumulative. I always thought I would learn more as I continued through life, but it seems the opposite is happening. Each time I find out something new, I only realize how much more knowledge there is out there that I don’t know. It seems that the realization of the lack of knowledge is what accumulates, not the knowledge. I thank the Watson for this realization, and many others, and I plan to dedicate the rest of my life to accumulating more ignorance.