Second Quarterly Watson Report

Since the last report, I have moved quite a lot. I stopped in Paris en route to Bamako, for vaccinations and visas. In Bamako, I felt confused and disoriented for a while -- this was far from the Mongolian steppes, their pure air and vast spaces. This was crowded and pushy and hot. Right as I was planning to leave, I caught a cold that kept me longer. This annoyed me, but in retrospect, it wasn't all that bad: I learned a lot about how nomads are perceived by the sedentary people they share a country with.

History and Circumstances

Nomads are increasingly defined by the sedentary people that constitute their countries' governments, and in Mali this power structure helped usher in the Tuareg rebellion of the nineties, and still causes discontent in the country's nomadic north. An interview with Aboubacrin Souleymane Haidara, the director of the Bureau for Environmental Conservation in Menaka, confirmed what I had perceived as a common attitude towards nomads -- one that on the one hand romanticizes and on the other reduces nomadic life to a fiction of the past. The interview also revealed that from a government perspective nomads are, simply put, a hassle. If disaster strikes, the government is responsible for bringing aid to its population, and this is obviously much more difficult to do if said population moves in search of pasture, or as Mr. Haidara put it, "follow the grasses and the winds wherever they want." He used the famine in Niger two years ago as an example, essentially saying that nomads gave the government of Niger a bad name -- by being inaccessible, and by dying, these nomads made it seem as though the government did not act fast enough, or enough at all.

I asked Mr. Haidara if really he believed that nomads should be settled, and he decided to explain Mali's strategy of "encouraging semi-sedentarization" to me. He told me that you cannot force a nomad to settle, but that "history and circumstances will show nomads how hazardous their lifestyle is." He believes that nomads are attached to their culture because it is a pleasant life, with its freedom of movement and star-covered skies. In reality, a nomad's life in this part of the world is far from easy, and many families I have visited eat only one meager meal a day. As one head of household put it, "a nomad is the most tired man there is. He always has to follow his animals, and look after them before he looks after himself." Semi-sedentarization means that the government encourages nomads not to move as much with their animals, and to spend at least one or two seasons in or around villages, where they have access to health centers and sometimes a little aid. This way, Mr. Haidara and others like him hope that "the nomads will come to reason." With the help of disappearing vegetation, draught, and poverty, the policy will probably work.

There is No Place Like Dairy

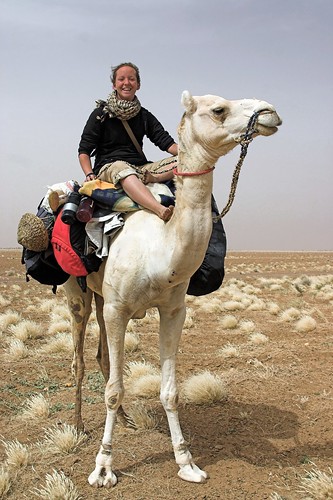

I spent two weeks en brousse with a family outside of Aguelhoc, some 400 km north of the desert town of Gao. I conducted some interviews up there, and then continued at various distances from the town of Menaka, in the south of the north. Much of my time with Mongolian nomads circulated around the milking of animals, and the subsequent processing of dairy products. Here, the animals are different -- I met no one in Mongolia who milked their goats, leaving all the milk for the young animals to fatten up for the always approaching winter. Also, there are no horses here, or yaks, but plenty of camels and donkeys. The resulting milk products are different, too, but watching Mohammed the herder bring container after container of sweet, frothy milk to the evening camp fire, and helping shake a milk-filled goat skin every morning to turn it into butter, I felt strangely, profoundly at home. The many differences remain, in some strange way, only superficial.

One of the reasons I decided to go to Menaka was the Ansongo-Menaka wildlife reserve, which most modern maps show as taking up much of the southern Menaka region. Unfortunately, the reserve turns out to really only exist on paper, dating back to colonial times, which explains why I had such trouble getting information about it. Nonetheless, Menaka is often referred to as the capital of nomads, but based on what I have observed, this name might also be reduced to paper-status before long.

Poverty Trap

It seems to me that the families that are a little better off -- the ones where the kids have plastic toys, the mothers wear sneakers, and the fathers listen to shortwave radios -- are those that remain more purely nomadic, and who move longer distances. What I am struggling with is the direction of causation. Are they better off because they move longer distances, and find better pastures for their animals, or do they move longer distances because they have the means to do so, and because they have more "money in the bank," in terms of more animals.

If a family has 7 goats, a long trek is a large risk, because you might lose 4 of them, more than halving your reserves. This is a risk you cannot afford to take, even though the few you would have left would probably be healthier and more productive as a result. Those goats are your bank account, and if the year turns out to be a bad one, without wild grains and berries, you still have to feed your children. You have to make a withdrawal, and sell some goats to buy rice and flour. So you end up moving short distances, often not very far from a village or town, to the detriment of your animals' health, and the amount of milk they give.

It is a bit like a nomadic parallel to the poverty trap, where, for example, poor families are forced to eat the grains they should be planting, and it is a vicious circle from there on, a hole out of which it is hard to climb. Less productive goats means you have to sell more of them to compensate for the dairy products they aren't producing, binding you more and more to villages and towns. And it certainly doesn't help if the government in fact prefers you to stay put, handing out aid only to people in and around towns, telling nomads that they have to fend for themselves if they choose to remain mobile.

Aid and Education

My biggest difficulty thus far, in terms of interviews and relating to people, is paradoxically enough international aid. I sometimes suspect that families, particularly those close to villages, exaggerate the difficulty of their situation because they think I can give their name to an NGO or an aid organization, increasing their share of the pie. This is not to say that they are not poor, simply that their answers might sometimes be slightly biased by their perception of who I might be, and what I might do for them. I have often left interview sites feeling rather lousy, as though I did not live up to some sort of expectation -- of aid, of promises, of provisions.

Only once has a family refused to answer questions (mainly because they were not Malian, but Libyan, and afraid that I would report them to some sort of authority), but I have repeatedly sensed a hint of disappointment when families realized that I had not come with sacks of rice or powdered milk, or clothes for the children. I can live with that, but what is really difficult is the realization that international aid might be what provides the final blow to nomadism in this part of the world -- families cannot afford to stay away from towns and villages, because that is where aid arrives.

Another positive force with a negative impact is education. Many nomad children are in school, probably a higher percentage than among the children in my neighborhood in Bamako. Many parents proudly fetched the notebooks of their kids, and many children aspire to be school teachers and doctors. This is certainly a positive trend, but not a single child I have spoken to actually wants to remain a herder, and they go to school to get away. The negative impact that this might have is that coming generations of nomads will be those who did not succeed in school, those who were left behind, people who do not want to be where they are. Hardly a recipe for a harmonious community.

Even though this reads like a very negative report, my personal experiences have been very positive. It is the future of nomadism that I am not optimistic about, not in any way my stay here. I am learning a lot, and I have met truly amazing people, and I am not looking forward to leaving. I am looking forward to going other places, but I will be leaving a part of myself in the Malian desert...

No comments:

Post a Comment