The Distrust Is Mutual

This morning I was telling Fa, the brother of the Moussa whose grandmother's house I live in when in Bamako, about my trip north. He interrupted me quickly to say “Me, I am afraid of those Tamashek.” He squinted until his eyes were narrow slots and added, to strengthen his argument, “Their eyes are like this.” On the bus from Gao, three Tamshek siblings took me under their wing, and coached me at every stop to hold on to my bags, watch out for my things, don't let anyone near my belongings, and just about every other variation on the theme. “You can't trust these people,” exclaimed Ibrahim, the oldest of the three, and when we arrived to Bamako, he took Taximan aside to tell him to “take her home correctly!”

Last night the American ambassador to Bamako hosted a reception (long story), and although I think he was genuinely disinterested in my person, he was at one point cornered by someone else into talking to me. He had overheard that I had just returned from the countryside, and the logical follow-up question was where from. So I had to answer. I didn't have to add "...exactly where the US State Department website tells you not to go," but I did anyway. He didn't talk to me any more, apart from the obligatory glad you could make it.

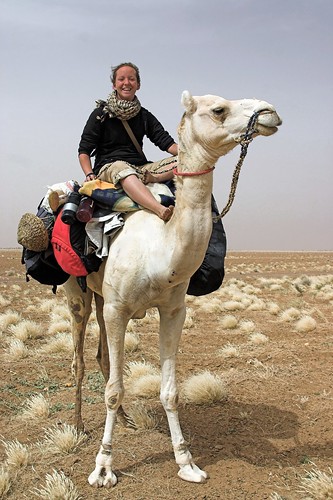

This photo is of the biggest bandit I met up north... Click on it for the story :)

On a more serious note, quite a lot of propaganda gets thrown around. As someone I met in Gao (and who... errm... let's just say he should know) put it: "If you run into the rebels, they'll give you some tagella and water and show you the way if you are lost."

So I have been in Bamako for a few days now, and tomorrow I head back out, to go hunting for elephants. Relax, the only thing I'll be shooting is photos, but it is a hit or miss mission, so I call it hunting. I really feel as though I ought to report to Watson headquarters to tell them I have crossed an international border, that's how different the south is from the north. Like when I first got off the bus in Gao the thought crossed my mind that I really need to locate a bank to change money in. I couldn't wrap my head around the fact that I was still in the same country. Anyway, even though the differences, and their implications for what president ATT called “the integrity of our nation” on TV the other day, are very interesting, this is the tale of my (continued) adventures in the wild north.

(This photo is actually from Tigerwen, an hour or two out of Gao on the way north, but it's purrty)

The Capital of Nomads

After my last note from Gao, I continued on to Menaka to do interviews with a guide named Vieux, which means old. In Bamako, I had gotten used to calling people by their occupation or some other characteristic, rather than their name -- “Shopkeeper, wake up, I want to buy bread!” or “Old Woman, is Moussa at home?” and “Take-Money, I want to get off here.” (Take-money is the guy who collects fares on the madness they call public transportation)

The school director in Adiel'hoc introduced me to another aspect of name-replacement when he called on a sixth grader by the name of La Vielle, or “the Old One.” I thought, hey, she's not very old, and he explained that the oldest child of a family often goes by the Old One, or Old, instead of their given name. Vieux Guide often complained about the responsibilities that came with being Old. Especially around Tabaski it is hard, because he has to buy a sheep not only for himself, but for his mother and brother too, because everyone needs to sacrifice a sheep, and sheep are expensive. Overall, it seems like people here, like in the West, spend most of their time stressing out about holidays, and essentially only enjoy them once they are over.

Menaka is often referred to by its inhabitants as “the capital of nomads,” an appropriately contradictory term. Its streets are sandy, and many families spend part of the year in town, and a season or two out in la brousse. People cherish their identity as nomads, and as Baka AgOmar, an artisan, put it: “Even us, now, we are nomads, we just stay in place.”

Menaka is growing rapidly, and will soon have electricity to go with its high-speed internet connection. The electricity will light some lamps and attract some insects, but what will draw nomads into town is more likely the prospect of aid than the comfort of running water and street lights.

We Don't See the Aid

Rahmeta Walet M'barak is an old lady who lives within walking distance from Menaka. (Keep in mind that “walking distance” is relative – one day I walked a not-very-far distance of 25 km) Her family used to trade salt from over by Yemen, but ever since the droughts of 1973-74, she has been living around Menaka. They came to the region because “the French were dropping grains from helicopters,” and she has stayed in the vicinity ever since. She lives with her sister, and the two of them depend largely on the husbands of their daughters for food.

She could list every major aid project in the past fifteen years, complete with what the aid consisted of, and what year it took place in. She remembers one in particular that took place right before “the year of the first bullet,” meaning the first bullet of the Tuareg revolution, which was fired in Menaka in 1990. The project gave each family grains and milk and oil and sugar. Since then she has heard rumors of aid, but once they get into town, they don't see the aid.

She is not alone. Many families have to choose between remaining purely pastoral and risk missing out on the aid that might come, and moving into or close to towns to the detriment of their animals' health and eventually to their pastoral livelihood. And government officials – conditioned by a training and prejudices that tell them that pastoralism is hazardous and a practice of the past – take advantage of this.

On my fourth day in Menaka, Vieux hired a motorcycle so we could reach some campements further away from town. As we zigged and swerved along a sandy road, lined with crouching acacias and skinny spurges, we happened upon a group of three men in flipflops, herding their goats. We stopped to greet them, and as we drove away, Vieux told me they were on their way to Niger with their animals. Niger? It boggled my mind that they were walking to another country with only plastic one-dollar-flipflops and a herder's cane as their equipment, but Vieux nonchalantly said “They've got a donkey further ahead with a little food, and they said they really have to find better pasture for their animals.” So much for nomadism being a “pleasant life,” as Mr. Haidara put it.

Part II

Loving Nature

Back in Gao from Menaka, Badi's brother, Al-Houseini Abdel-Moumen Faradji, who is starting up an NGO called Amour de la Nature (Love of Nature), and whose roof I sleep on when in Gao, introduced me to Odile. Odile is a 54-year old French woman who used to live in Cote d'Ivoire, and who was going with Housein to see some of the campements he works with... correction: will be working with.

Odile has traveled quite a bit in west Africa, and isn't big on sleeping comfortably or showering regularly or drinking bottled water, so we got along quite well right from the start. Their plan was to record folk tales and music and my plan was non-existant at that point, so why didn't I come with them? I thought it sounded good, so the next day we headed out.

We began by heading up to Adiel'hoc, which allowed me to greet my family and properly say bye to the place, and for Housein to see his family, most of which he hadn't seen in years. Housein would deserve a whole chapter of his own. Thing is, his NGO hasn't actually received any funding yet, and by consequence, like so many other projects, his is still in the vague, un-realistic, dreamy phase. So Housein doesn't have any money either, not even enough to leave Gao most of the time. He lived for a long time in France, and might have eaten more than his share of philosophical soup, but his ideals and ideas are in the right place, and he is full of stories about mercenaries in Libya and rebels in the mountains.

Around Adiel'hoc, we visited a site with rock carvings of giraffes and ostriches (!) that gave me time-vertigo, and another place where spring water gathers in little pools, surrounded by black rocky desert. That was Odile's vacation, and when that was done she said “Finished, the tourism. Now let's work.” We hitched down to Kidal with a jeep, our eyes widening at the contrasts between the beige sand and the dark contours of the Adrar, a mountain range leading all the way up to Algeria. Once there, we startled everyone in the family where we spent the night by choosing to sleep outside in the courtyard, rather than inside the house. Here in Bamako the mozzies would suck me dry, and there is no place to hang a mosquito net outside, so I make myself sleep inside, but I think I have contracted a serious case of claustrophobia in the past few months.

Equalizing Trucks and Ochre Valleys

From Kidal we continued on the most common “public transportation” in the north: a gigantic red truck, into which we loaded some 60 passengers and their luggage. I was surprised at how comfortably we rode, but when we got off in Anefif and stretched our scrunched limbs, I realized that I did not envy the Nigerians next to us who were continuing all the way to Bamako on the same vehicle.

From Anefif to... the desert, we hitched with white Renault truck, which had been remodeled into some sort of camper, the whole back part covered with wooden boards painted baby blue. I baptized it “the equalizing truck”, since no matter what color the passengers are going in, they all come out the same color. We could see through the back doors that there was air out there, somewhere, the problem was that none of it made it into our lungs for all the dust that floated around in the truck.

We got out in the middle of a desert that looked just like all the other desert all around us, but Housein said “It's here,” so we took his word for it. It was indeed there, the only problem was that the campement that was supposed to be there had moved elsewhere. So we spent the night under an acacia, filled our water bottles in a “well,” which in reality consisted of an oued where you dig twenty centimeters and reach water. The next few days were spent visiting Moor families, drinking tons of milk and eating tons of goat meat.

One of the campements I will never forget. We had walked quite far to get there, with heavy bags and increasingly hot sun. We entered a valley, which in Moor is known as “Oued al-hamera” -- the valley of ochre, because the ground is covered with dark ochre-colored rocks that nomads use to color the hide of their tents. Sheltered by a few bushes and a wild date tree lived a little three-person family – M'neha, Zeina and their son Hamed Salem. When we approached, Zeina covered her face, and ululated to welcome us. M'neha shook our hands and was still shouting welcoming phrases to Housein when he rushed off to kill a goat. Hamed Salem smiled, dug around in his pockets, and handed me a flint arrow head he had found.

Moor campements are very similar to Tamashek ones – they are essentially the same people, just that the Moors have been more heavily influenced by Arab culture and Islam, and the women tend to cover their faces a bit more than Tamashek women. On the other hand, Moor women smoke, which is pretty much unthinkable in most Tamashek families, where women instead shik, i.e. stick tobacco mixed with ashes in their cheeks.

When it was time to head back to Gao, we had moved between campements on foot, with donkeys, and the last two-hour stretch to the road we made on camel. One of my knees was bothering me a bit from the previous day's 25-km walk through sand, so we loaded me onto the camel with the bags. Once we reached the road and rested a bit, the camel's owner handed me something. I took it, and couldn't quite figure out why he had handed me a piece of shit. Literally. It was a piece of camel's dung, and he giggled as he told me it was my camel's license...

We spent the remainder of that day waiting for anything to come by on this supposedly “main road,” but nothing moved but the sun. By the time the sun was casting long shadows, we began preparing to spend the night, gathering twigs for firewood and sweeping away the acacia pins where we would sleep. And then a truck appeared on the horizon. We jumped up and down waving our arms, but it showed no sign of stopping. My theory is they were just so surprised to see these two white women and a Tamashek waving their arms in the middle of the desert that they didn't believe we were really there until they got really close. Then they stepped on the brakes and told us to climb in.

The truck was a German MAN-truck that I quickly named Azalai (this was quite the vehicle-naming trip), the name of the salt-trading caravans that used to transport salt between the infamous salt mines of Taoudenni and Timbuctu. Trucks like our Azalai are exactly what killed the caravan (but didn't kill the deputy) – it was so heavily loaded with fossil salt bricks from Taoudenni that even at 30 km/h, the shocks couldn't cope with even the tiniest bumps. We spent the evening waiting in Al-moustaghat, a tiny town that everyone en route to and from Gao passes through, and where “the matches cost 50 francs” (twice the normal price). What we waited for was a satellite phone call that would inform our driver that the Boss was done negotiating with customs, and in the meanwhile we cooked pasta and sardines, made tea, chatted, made some more tea, and finally drove off into the night. In the middle of the night, we stopped somewhere to sleep, and got to Gao the next morning. Exhausted and with bruises from lying on top of salt bricks an entire night, but we got there!

Folk Tales and Tradition

A group of women in Anefif shared folk tales and fables with us, and I will share a short one with you, as it relates to transportation: The donkey, the goat, and the dog were going to town. It was a hot, dusty day, so they decided to share a bush taxi. Once in town, the donkey paid his fare and got out. The dog only had a big bill, and the goat didn't have enough money on him, so the driver kept the dog's money and drove off. Ever since that day, when bush taxis ply the roads, the donkey stubbornly stands in the road without budging, since he already paid. The goat bolts and runs quickly into the bush, since he owes money, and the dog chases the taxi barking give me my money, give me my money!

We also got to talk to a group of Fraction leaders (the tamashek political system of families and what used to be “tribes” but are now re-organized into fractions is really complex, but suffice to say they are important men in their community) one evening, and I asked them towards the third round of tea what they thought was going to happen to nomadism in the future. One thing that has been discouraging me, both in Mongolia and here, is the fact that young people who go off to school don't want to be herders, and young people who don't go to school don't want to be herders, but are forced to because there is nothing else they can do. Essentially coming generations of nomads might consist largely of those individuals who did not succeed in school, those who were left behind, people who do not want to be where they are. Hardly a recipe for a harmonious community.

Alwata Ag-midi, Chef of the fraction Imakoran I, responded cryptically. I was dressed in a colorful traditional toungou, an all-in-one robe and veil, and he said: “If you come en brousse dressed in toungou like that, a man will see you and pull his turban up over his face before he approaches to greet you,” and he covered the lower half of his face with his turban, a gesture Tamashek men do in front of people they respect. “If you come dressed in pants, he will say 'whatever' and leave it,” he added for clarification. I thought it was a nice way of saying that even if Tamashek values, and nomadic lifestyles seem to be changing, between Tamashek the values remain.

Tawwad Ag-Haballa, Conseiller of the fraction Idnane, answered with a saying: “No matter what the weaving, it will always remain straw and strings.” By this he meant that a thing doesn't change it's nature, and those young folks who seemingly leave for towns and cities will always be nomads. He believes they will come back to help their communities, as veterinaries, teachers, and doctors. They will come back, better equipped and more knowledgeable than they were before, but they will come back nomads.

With this I leave you to go pack my bags for the wild elephant chase.